Published in Neue Zürcher Zeitung on September 30, 2006

Text: Bernadette Calonego

Photos: Elaine Briere (www.elainebriere.ca)

Looks like it`s going to be a quiet day, chief pilot Carl Benson says. Then the phone rings. The fuel tank of the seaplane is filled up immediately. Ten minutes later, two inconspicuous men enter the building of Inland Air in Prince Rupert.

They are undercover agents of the Canadian Ministry of Fisheries and Ocean – officials on a secret mission. They are on the hunt for poachers on the Northwest Pacific coast who are harvesting protected abalones from the Pacific and selling them for 80 dollars a pound.

From the air, one of the agents says, the poachers` boats look like “giraffes in the middle of New York.” The seaplane will not follow the boat, it will fly normally so as not to rise any suspicion. This is a job for an experienced bush pilot. Not much later, Carl Benson and the agents taxi out of Seal Cove Bay with a DHC-2-Beaver. The plane takes off with a roar.

Meanwhile, Bruce MacDonald, owner of Inland Air, tanned and wiry, examines the flight plans. All his pilots, Dave, Garry, Carl, are air-borne now. They are experienced men who Bruce knows very well. He employs only outstanding pilots who can handle the difficult weather conditions on the Northern coast of British Columbia. Out there, anything is possible. Out there, the weather can change in a heart beat.

Any pilot who does not do the right thing when walls of blinding fog are approaching, when winds double their force in the twinkling of an eye, forcing the plane to dance like a puppet he, he finds himself in a death trap if he cannot find his way out in time.

The unpredictable weather, says Bruce, makes this area one of the most challenging for bush pilots.

However, the people living here cannot exist without seaplanes: the inhabitants of isolated settlements far out in the ocean, marine biologists, health officials, power plant engineers, road workers, loggers and sports fishermen, students on their way into town, aboriginal elders with their grandchildren, patients needing urgent treatment in the hospital.

They all fly, trusting completely in the pilot`s judgement and experience. “We cannot afford to have one single accident”, Bruce says.

His index finger moves and hovers over the well-worn map on the wall. He taps it again and again on the tangle of inlets and islands. There and there and there. In these five locations, friends in seaplanes have dropped in the ocean. Dead, all of them. On the sea, Bruce says, the victims usually drown in the mangled wreck near the water`s surface. They become disoriented by the crash and cannot find their way out of the plane.

Inland Air has been in business for 26 years, so far, nobody has perished.

“We pilots are prima donnas. We are good at what we do because of what we are. We know that we are good but we don`t brag about it.”

Bruce MacDonald (54), a pilot for 35 years

Bush pilot Dave Norman looks out over the seaplane base in Seal Cove. Bald eagles are circling. Dave`s gaze freezes. He has spotted something on the dock where the planes are moored. He storms into the Inland Air building, returns with binoculars and spies through the lenses. But he does not scan for dangerous swirls in the water or for an approaching weather front. Dave has spotted a pilot from his North Pacific Seaplanes competitor who is wearing its official uniform.

Inland Air and North Pacific operate from the same base in Seal Cove.

Dave slowly lowers the binoculars. “I cannot believe it”, he says, “Dale has got a monkey suit on!” A true bush pilot does not dress up. Proudly wearing his blue jeans, wide suspenders and a striped T-shirt, Dave stomps down to the dock.

Sometimes, he says, the passengers walk past him when he is waiting for them in front of the seaplane. “I am sure they are looking for a tall, blond, handsome man in a uniform.”

But when Dave`s rumbling DHC-2-Beaver surges into the air, he leaves no doubt about who is the king of the skies, as on this sunny, clear flight day, so untypical for Prince Rupert. Nevertheless, Dave is on his guard. A seaplane can disappear within seconds from sun into fog. That would be fatal, because the pilots use strictly VFR – Visual Flight Rules: The pilot can only rely on his eyes and on what he sees.

Dave pulls handles, turns knobs. “Flying in this area is like an algebra equation with fifteen variables”, he says. In his mind, he has to watch many numbers all the time: speed limits, temperatures, fuel reserves, sight, other aircraft, air currents, pressure, his own condition, the tide – a crackling voice in his head set cuts him short. There is a grin on his face. “Flight service has just told me from what direction the wind is blowing – as if I did not already know! I only have to watch the waves.”

From now on, Dave is on his own. No radar, no control tower. Only a small screen in front of him: the GPS shows the Beaver`s position. But nothing, Dave says, replaces the pilot`s good judgement. Dave`s company, the small charter airline Inland Air, would not take anyone who has fewer than 2000 flight hours – 6000 flight hours would be ideal. It has become increasingly more difficult to find experienced pilots for seaplanes.

All the men working for Inland Air are 50 or older. Young pilots finish their flight school with approximately 200 flight hours – not adequate enough for a job on the West Coast. But without a job in an established company, they cannot acquire experience – it becomes a frustrating Catch-22 scenario. As they are denied a future in this occupation, they would-be-pilots leave the area.

Dave sees clearly the final consequence: “This era of flying comes to an end.”

In his Beaver, only three of the seven seats are occupied by tourists who want to see the grizzlies in the Khutzeymateen valley.

With such low weight, the plane sails through the air like an eagle.

“In ten minutes you can get lost because the mountains look the same, the rivers, the terrain look the same, no roads, no houses, no people.”

Ken Cote (56), a pilot for 35 years.

Dave steers towards the snow-covered coastal mountain range. He skirts the walls of granite that drop off steeply, flies above mountain lakes, sparkling bluish remnants of glaciers glittering in the sun.

Dave turns his head. He recognizes it once again on the facial expressions of his passengers – their quiet awe in the face of this monumental beauty, their emotions – and their nervousness. A tiny flying-machine in the eternal space. Nothing but air between a thin sheet of aluminum and the abyss.

Dave allows the wind to carry the Beaver up to the mountain ridge. For a moment it looks like the plane is about to scratch the face of precipice. But the up-current lifts it elegantly over the ridge. Then the pilot abruptly turns the metal nose downwards. He shouts “Now we are going over the edge” and the Beaver dives into the void.

Before the stomachs have settled down, Dave points out white mountain goats running on the bluffs below: “We used to come here and hunt them, I thought we`d wiped them out.”

Ten minutes later, he prepares for landing on the Khutzeymateen Inlet. Now he is completely absorbed. He does not chat anymore. Landing is the most critical moment of the flight. Deadly dangers lie in wait. Perhaps there is a log under the surface, a hidden rock, a sandbank in shallow waters. Beware of rolling waves. Even worse: a surface that is smooth like a black mirror. The pilots call it “glassy water”, a mirage can sometimes cause them to crash into it because they cannot estimate the vertical distance. Finally, watch out for that killer whale who might just emerge along your landing path.

Dave flies an exploratory loop, while scrutinizing the surface. Then he puts the floaters softly down on the water just as a pastry cook smoothes whipping cream on a cake.

The plane glides to a makeshift platform where Garry MacAuley`s Beaver is already moored.

“Bush pilots aren`t the cowboys anymore they used to be. Years ago, you would push it a little bit harder. Today, we turn around all the time because of weather.”

Carl Benson (57), pilot for 38 years.

Returning to the plane, Garry`s passengers are beaming, they have seen six grizzly bears. Gary is beaming, too, but he keeps a steady eye on the wind sock. Fifteen knots is still for a take off. At 25 knots, he would have to taxi further out of the inlet where the wind will not be as strong.

“It was whirly”, he informs Carl Benson later in the office of Inland Air. Carl who hovers over the flight plans tells Garry about his next job: a flight over Hecate Strait, infamous for brutal storms, to New Masset on the Queen-Charlotte-Islands. The distance is about 130 kilometers or 45 minutes. Six sports fishermen are waiting there with plastic-sealed salmon. They don`t know that the pilot who will fly them used to be an evangelical minister.

Garry studied philosophy and theology in Switzerland. He loves being close to heaven. On the Fiji Islands, he used to fly such celebrities as former Beatle Ringo Starr. He has also lived and flown in New Zealand, Japan, Mexico and Argentina but he says the area around Prince Rupert exceeds all previous challenges. Winds of 100 kilometres an hour; sudden weather changes; whipping rain that hammers the hull of the plane. The tormented engine coughs dangerously as the Beaver jumps up and down in the storm. Fog thick like insulation wadding when the cold glacial air from Portland Inlet meets the warmer current from the Pacific.

Always be prepared for a bad surprise. Adrenaline in your blood.

Garry runs down to the dock; a life in constant motion. “It is kind of a lonely life”, he says. Garry is a bachelor.

A black car stops in front of the office, a man jumps out, a doctor from one of the cruise ships travelling from Seattle to Alaska. There had been an emergency and the doctor had to accompany the patient to the closest hospital which happened to be in Prince Rupert. Now he wants to catch up with the cruis ship in Ketchikan, Alaska.

The people from Inland Air hasten to prepare the documents for the cross-border-flight.

Paperwork. Paperwork. Paperwork.

Bruce MacDonald paces like a tiger between the office and the check-in-counter, looking for insurance papers. Since he has become owner of Inland Air in May 2006, the added responsibility weighs heavily on his shoulders. “I`ve just got an invoice for the last 3 months”, he says: “28,000 dollars. And another 10,000 dollars taxes for the company buildings.” How was a small airline like his ever going to survive?

“Coastal seaplane pilots are an endangered species.”

Dale Leekie (58), pilot for 38 years.

Bruce steps outside, lights a cigarette and blows smoke in the air. He recounts how flying of seaplanes has changed over the last 50 years. In the pioneer era, the pilots used to leave “a trail of death and carnage” behind them, as Bruce describes it.

Dave is sitting on a bench nearby and feeds himself and a dog with crab meet. “It was all about showing off to the other pilots”, he says and cracks the red shells with his bare hands. “They wanted to outdo the competitors.”

As a young man, Bruce was a bush pilot in the Arctic, he learned his skills from the pioneers of the trade who carried boots, a thick coat and a knife. Back then, Bruce did not fly without a sleeping bag, a bottle of whisky and – just in case – a gun. One day, his Otter blew a cylinder and he was forced to land in the middle of the Barren Lands. He waited four days for help until an Air Canada pilot who flew over the North Pole on his way to London, England, intercepted his SOS signal.

Many pilots would not escape so luckily. When the number of accidents skyrocketed the Canadian government intervened: In the early eighties, new safety measures were put in place. The intoxicating but dangerous freedom of bush pilots was reigned in.

Bruce walks to the hangar where engineer Joe Hidber is painstakingly checking out a Beaver. Every 100 flight hours, the planes are taken out of the water and examined for potential damage.

The Beaver is a Canadian myth – and a fossil. The production of this seaplane ended in 1967. Of the 1692 Beavers built, close to 1000 are still flying today. There is no substitute for the Beaver. The pilots love her passionately but the life span of this type of plane is coming to an end. She has perhaps another ten or fifteen years left to fly. Recently, Hidber says, he repaired a 1948 Beaver that was as old as he.

“What we need in a pilot is a humble person. When you think you can get away with everything, you shouldn`t be in a seaplane.”

Dave Norman (55), a pilot for 28 years.

Dale Leekie is flying to Hartley Bay for North Pacific. He wants his Beaver to gain height. “We have an inversion here”, he says. The sun has been heating up the rock faces of the mountains below and, after several sunny days, warm air is rising and causing turbulences.

One of the passengers, Faith Turner, a nurse, puts the headset over her graying hair. If she had a patient with lung punctures who could not bear air pressure, could the plane fly in lower altitudes? she asks the pilot.

Throughout her life, Faith had often entrusted herself to these small planes. As a child she flew in the Arctic where her British-born father was a missionary, and later as a nurse in Canada`s most isolated areas. When she once took a pregnant woman to the nearest hospital, she had to implore the pilot to fly straight because the ups and downs would have precipitated labour. Faith is replacing a nurse on leave at the nursing station in Hartley Bay.

165 people live in this Tsimshian First Nations community, a tribe who had inhabited this region for more than 5000 years. It is 45 flight minutes to Prince Rupert, a village without roads, doctor or shop. “And hopefully no acute appendix”, Faith says as she looks down on the glistening ocean.

She has brought with her a two week`s supply of food and a warning of another nurse that the flight to Hartley Bay had been her worst trip ever, with a churned-up sea and frightening turbulences.

Dale nods. Huge waves often roll into this bay and make the landing difficult. Before leaving, he had checked the Hartley Bay weather conditions, transmitted by a webcam at the local school. The landing area was clear.

Dale is not a dare-devil. His father, a hobby pilot, perished in a plane crash when Dale was a teenager. “I like it when people have nothing to talk about after the flight is over”, he says. “I don`t want excitement.” Wishful thinking: While climbing out onto the dock after a soft landing, a passenger`s cell phone drops into the water and disappears.

“I have only met very few female bush pilots. I think it has to do with the fact that women have to take care of their families.”

Virginia McRae, airline receptionist for 20 years.

Port Simpson. The silence there strikes you. There are no screaming children, no hammering noises from workshops, only the piercing cries of bald eagles pushing themselves off the roof tops to vanish on the misty horizon.

The old fortress of the once-mighty Hudson`s Bay trading company no longer stands in this bay. The remains burnt down in 1915. The cannery on the shore has been shut down and the dusty roads leading nowhere are empty. The First Nations people call their village Lax Kw`alaams, “Island of the Roses”.

Far out on the Pacific Ocean there are small dots, the boats of the fishermen swiftly casting their nets because the government has allowed fishing for just a few hours. Too little time, to make a living. Suddenly, a buzzing sound. Northwest Pacific flight 101. The connection to the outside world. A 15 minute long life line. Three daily flights are scheduled for the 1000 people in Port Simpson.

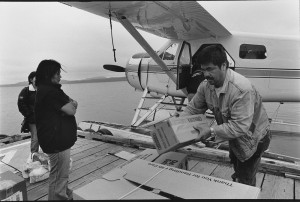

Sometimes the seaplanes do not arrive. None could land a week ago when the fog pressed down on the ocean like the lid of a coffin. Gillie Sankey climbs cautiously out of the DHC-3 Turbo-Otter. Despite her old age, the First Nations woman shops twice a month in Prince Rupert because the groceries are cheaper.

“There are bears in town, that`s why you don`t see any people on the road”, she says while the pilot heeps the freight onto the dock.

Bob Bernhardt, a pest-control expert, is not deterred because he comes here every month. Today he has to spray the houses of the none-native teachers. Accompanied by two electricians who flew in with him, he walks up to the local band office.

In Seal Cove, North Pacific Seaplanes owner Gene Story looks through the window. He would like to be optimistic but the future worries him. “The young natives move to the cities, the families stay away. The population in the North decreases every year.”

A decade ago, there were 23 seaplanes in Seal Cove, now there are only 10. During that time, fishing and logging companies booked many regular flights but today they are facing hard economic times. Furthermore, Gene Story says, roads are being built into isolated communities and helicopters are taking away business from the seaplanes.

On the other side of the bay a Beaver takes off. Bruce MacDonald is heading to a remote mountain lake. He is eager to take adventure tourists to some magic places. You have to be creative, he says. He would rather fly happy tourists around than grumpy loggers.

Dave Norman is sitting in front of a computer in the kitchen of Inland Air and looks at the weather charts. A flight to New Masset is on the books. “There is quite a load”, he says, meaning fog. “I might not go to Masset.” He stretches his broad shoulders and gets up. “It seems that whenever there is a tough job to do, they call me.” There is satisfaction in his voice. This is not a job for a tall, blond, handsome man in a uniform.